Stream Flow And Fly Fishing: Runoff and Hydrographs

You're getting ready for a long awaited fishing trip so you have an eye on the stream gages (footnote #1) in the area you plan to fish. Of course you have your other eye on the Weather Channel. No recent rain and no rain predicted – no problem. Recent rain or rain predicted – no problem? A little understanding about what happens as a result of rain or snow in the watershed you are going to be fishing will help you make a better decision.

We often hear the terms watershed, drainage area or catchments tossed around when we talk about stream flow. Some people aren’t necessarily comfortable with just what they mean. Leave it kids to break it down to its simplest terms. About 15 years ago, my two young sons were going to join me for the first time on my annual trip to Wyoming’s Encampment River area. I told them that we could go up on the Continental Divide. They looked at me rather strangely as I tried to explain about stream flowing into different oceans. Suddenly Ethan figured it out and explained to his younger brother that it was like the roof of the house and all the rain that fell on one side went down one downspout and the rain that fell on the other side when down a different downspout. Of course being a preteen boy you can figure out what he wanted to do on the Continental Divide!

A graphic representation of stream flow of some period of time is called a hydrograph. The hydrographs we are most interested in as fly fishers are the storm event hydrographs and the long term hydrographs.

Rain or snow that falls on a watershed either soaks into the ground or runs over the surface. The water that soaks into the ground makes it’s way into the stream much later is called base flow. How much soaks in and how much runs over the surface depends on a number of different factors including, how porous the ground is, how wet the ground was already, or how intense the rainfall is. A sponge is can be a good analogy for a watershed and what happens to precipitation. The sponge absorbs some or all of the water that lands on it. If it is thin it can only absorb a little of the water that falls on it. However if it is much thicker it will absorb much more. An area with only a shallow layer of soil or with rock outcrops is a thin sponge. If the sponge is already wet or saturated it can’t absorb more water. Like wise, ground that is already wet can’t absorb more water. And if the rainfall is too intense, the ground can not absorb it as quickly as it is falling and most will over the surface and into the stream.

Rain or snow that falls on a watershed either soaks into the ground or runs over the surface. The water that soaks into the ground makes it’s way into the stream much later is called base flow. How much soaks in and how much runs over the surface depends on a number of different factors including, how porous the ground is, how wet the ground was already, or how intense the rainfall is. A sponge is can be a good analogy for a watershed and what happens to precipitation. The sponge absorbs some or all of the water that lands on it. If it is thin it can only absorb a little of the water that falls on it. However if it is much thicker it will absorb much more. An area with only a shallow layer of soil or with rock outcrops is a thin sponge. If the sponge is already wet or saturated it can’t absorb more water. Like wise, ground that is already wet can’t absorb more water. And if the rainfall is too intense, the ground can not absorb it as quickly as it is falling and most will over the surface and into the stream.

Continuing the sponge analogy, it takes some time once we stop adding water to the sponge for it to become dry again. That is why the ‘falling limb” of the hydrograph is much less steep than the than the rising limb.

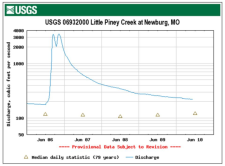

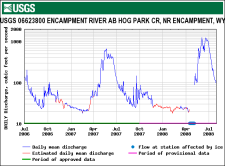

For those of us trying to predict when to the best time to make a trip to an area, the long term hydrograph is generally of the most interest to us. In fishing locations where water levels are primarily dependent on snow fall – Northern New England, the Mountain West and Patagonia – we can generally estimate fairly accurately when runoff from snow melt will begin and when it will end. Long term hydrographs from areas were snowfall is the primary source of precipitation have the shape of a series of wave. We want to time our trip so that it doesn’t correspond to the peak snow melt period. If we also look at graphs of snowpack (footnote #2) in the same area and know something about optimum water levels for fishing we can make an even better estimate of when to plan our trip.

For those of us trying to predict when to the best time to make a trip to an area, the long term hydrograph is generally of the most interest to us. In fishing locations where water levels are primarily dependent on snow fall – Northern New England, the Mountain West and Patagonia – we can generally estimate fairly accurately when runoff from snow melt will begin and when it will end. Long term hydrographs from areas were snowfall is the primary source of precipitation have the shape of a series of wave. We want to time our trip so that it doesn’t correspond to the peak snow melt period. If we also look at graphs of snowpack (footnote #2) in the same area and know something about optimum water levels for fishing we can make an even better estimate of when to plan our trip.

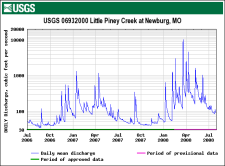

In areas where snow fall is not predominant form of annual precipitation, long term predictions of when will be the best time to make a trip are not quite as clear cut. While these areas may show a wave pattern, the spikes or short term variations are somewhat random during the rainy season and are much more important consideration in trip planning. In these areas, since short term changes in flow levels are dependent on localized rainfall events, often at the watershed level a back-up date or location is crucial.

In areas where snow fall is not predominant form of annual precipitation, long term predictions of when will be the best time to make a trip are not quite as clear cut. While these areas may show a wave pattern, the spikes or short term variations are somewhat random during the rainy season and are much more important consideration in trip planning. In these areas, since short term changes in flow levels are dependent on localized rainfall events, often at the watershed level a back-up date or location is crucial.

Footnote #1 See Fly Fishing Tip, Stream Flow And Fly Fishing: How A Stream Gage Works

Footnote #2 See Fly Fishing Tip, Snow Water and Predicting When to Take Your Trip